Taey Iohe

The Drifting Bed, Transference of Meaning, and the Emergence of the Constellation of Memories

by Young-ok Kim, critic

I’ll write to you, I promise: “I won’t write to you again.”

It is untranslatable to describe what you lost when you grew. That gap of untranslatability, perhaps, is why you are writing. Your attempt to bringing to life your wounds in the past, emotional discoveries and human stories are in the translation with the available words. But as for the shinga, it is better to leave it as it is instead of making the translation; there are always impossibilities and limits in translation.

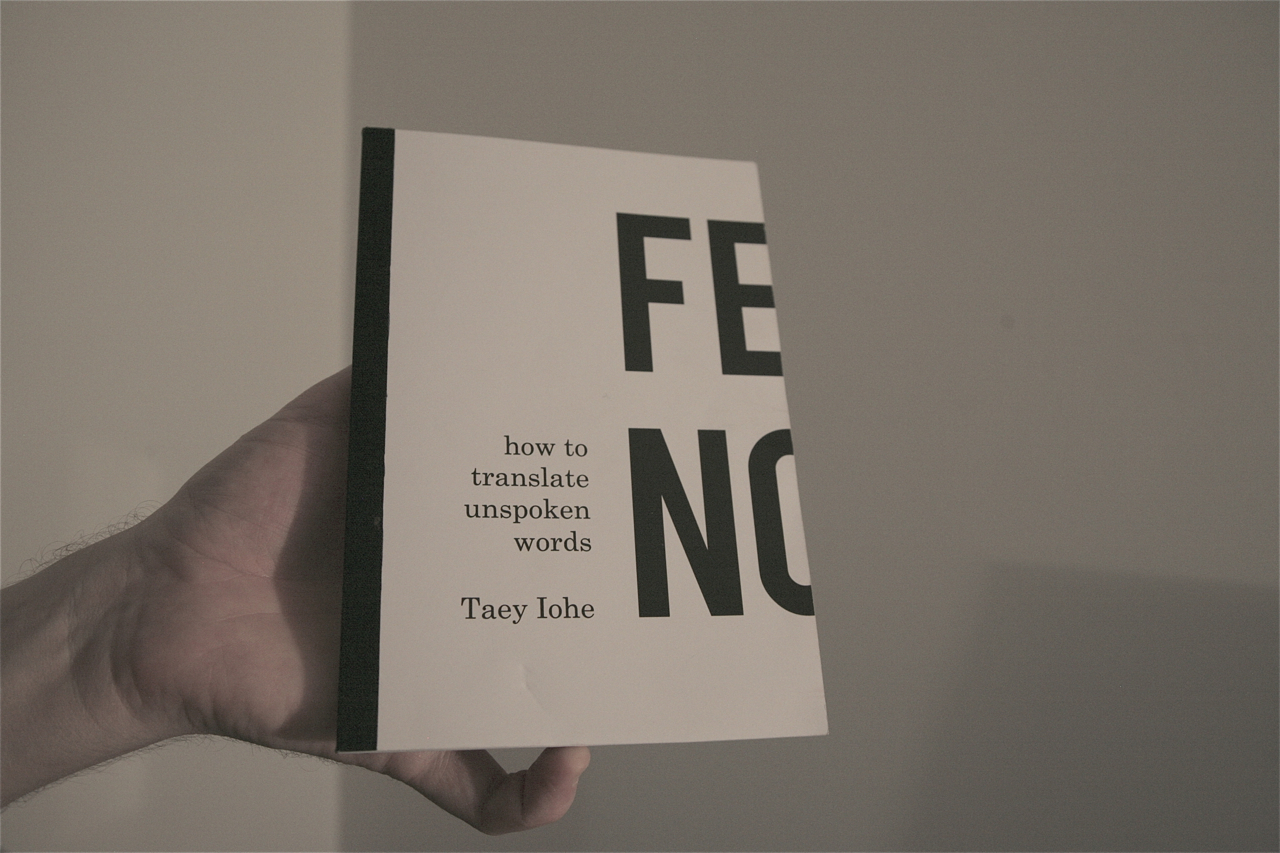

(Taey Iohe, ‘Untranslatable Shinga’ in Fear Note: How to Translate Unspoken Words, 2010)

Letter writing is important to artist Taey Iohe. While the themes of her works since the beginning of her career have focused on travel and movement, letters and the act of writing letters have been a key working method that has imbued her themes with a singular voice.

Let’s take a look at Strangers in the Neighbourhood (2007-2009), which includes various components such as photography, installation, video, and a workshop. As part of the special exhibit, Sister’s Back (Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, 2008), Sleepwalkers and Lure of the Lawn, which belong to Strangers in the Neighbourhood, were installed. A large room is paved with green grass, and a bed sits in the middle. The bed represents the place where Mary Wollstonecraft, who lived in eighteenth-century Britain, meets Na Hyeseok who lived in early twentieth-century Korea. Inscribed on the walls of the room are conversations and letters that Wollstonecraft and Na have exchanged. “There are so many stories to tell, hear, and share,” says Wollstonecraft, and Na, who has been traveling freely as a spirit since her death sixty years ago, confesses to Wollstonecraft, “I am now dead and free to go wherever I wish, but that place will always remain the place, and pain and sadness will always be here, close to my heart.”

Taey’s next exhibition, Namhaegeumsan: Southern Sea Silk Mountain (2011), includes a piece called “I won’t write to you again” and a letter sent to the artist by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982), who figures as an imaginary audience (ghost), in anticipation of her upcoming exhibition. “I won’t write to you again” reveals the process of text blurring and bleeding as a frozen flower placed on the letter melts. Through this process, the assumed permanence and uniformity of written languages is deconstructed. As the emotions frozen and trapped within the written words begin to thaw the perceived meaning of the text expands and begins to seep out. Hak Kyung Cha, the imaginary audience, carefully opens the door and comes into the gallery and looks at the pieces on the first floor, the basement, and then the second floor. Among the messages the artist has left for Cha is “You are very careful when you step forward across the thresholds, because you fell before.” And then in the blue darkness of the second floor, Cha slowly runs her hands over the walls, finds the felt beads on the walls like soft nipples, and finds a pair of black Wellington boots. “These might be my boots,” she imagines.

Lastly, the paragraph quoted in the beginning of the text appears in Untranslatable Shinga (2010). This text was published in Taey’s book project, Fear Note: How to Translate Unspoken Words. In this text, which takes the form of a letter written to Pak Wan-suh, the author of Who Ate Up All The Shinga?, Taey explores in depth the impossibility of translating the word “shinga”, a plant the author misses after she moves from the country to the city. Employing the signifier shinga, Taey expresses the “pain and sadness always pooling around her heart” as an outsider living in Britain. As Taey herself specifies, this feeling is different from homesickness and nostalgia for the specific geographical location that is Korea. This sentiment, which encompasses the distance between “there” and “here,” is passed on from Hyeseok Na to Hak Kyung Cha and then to Pak Wan-Suh and finally to Taey like an important feminine heritage of herstory. Joining this feminine heritage or herstory is Mary Wollstonecraft and the three immigrants living in London who share their stories in the three-channel video piece, Intraweave (2011). The flow of the stories they weave, distinct from a history built on linear time, produce a web-like space made of stories.

The ball of red thread on the bed where Hyeseok Na and Wollstonecraft meet, the ball of red thread in the hand of the narrator of Intraweave, and the ball of red thread on the bed of the photographs from Strangers In The Neighbourhood, seem to signify the passing on of a feminine heritage and at the same time the weaving and piecing together of stories. Lines remain like traces between one story and another, but these lines do not mark a boundary, but rather a fateful connection. Also, each story embodies many different sentiments, places, times, and boundaries of experiences. This narrative does not comprise a time-space of one complete story, but rather a liminal space that divides “there” and “here” and at the same time includes both. Taey’s works continuously evoke this space. This space calls upon the subject who lives within it and who simultaneously becomes the physical manifestation of this place. One must not be quick to assume that this is a cold space that embodies only pain and sadness. What should be emphasised, rather, is that in this space, heritage and memories are not only evoked and passed on, but also transformed and generated. This place is a linguistic body - a physical linguistic space.

Let us look at the specific example of linguistic space in Namhaegeumsan, a book of poems by Seong-Bok Lee that Taey encountered when she was around twenty, and its relationship to the physical-ontological space of Dictée, by the artist Hak Kyung Cha who lived as a female immigrant in the empire known as the United States. According to Taey, the location where this feeling seeps through and flows into is a psychological, aesthetic space called the “contranstellation,” formed by the countless legacies of traveling beds and sleepwalkers. “Contranstellation,” a word Taey created to convey this feeling, does not have an exact Korean equivalent. The word comprises a combination of “constellation” and the prefix “trans,” which means to go across or beyond (and which also echoes “translation”). Contranstellation emphasises the movement of a constellation that continuously changes. Also, by connecting the prefix “con” (together) with “trans”, the stability of the compound elicited by “con” is denied and interrupted.

Thus far, Taey’s works have circled around themes such as the body that travels across vastly different time periods and places/spaces, the language that breaks and splits upon encountering other language to give rise to mutantions and germinations, and liminal ways of life created by (in)visible borderlines. These various themes evoke many variations of abstract thoughts and sensual feelings. The abstract, conceptual ideas coupled with sensual feelings she elicits, and the coexistence of linguistic reflections and the awareness of the physical-ontological in Taey’s works are characteristics that merit continuous attention. For example, in Namhaegeumsan, Taey physically and sensually creates spaces with “thoughtful feelings,” such as She Went Through the Walls (installation with sound), Threshold Sea (installation), The Signer (video), andThe Strata of the Dialogue (installation with drawings) by employing various media and methods. The memories that are evoked and also newly generated in this exhibit embody a certain visceral warmth and wetness—a pale orange brightness and blue darkness. Rather than a complete denial of all opposing elements, here translation and mistranslation, recognition and mis-recognition, comprehension and incomprehension clash, mix, and repeat these encounters and give rise to a hybrid space. To me, Namhaegeumsan is an excellent act of écriture féminine. Above all, écriture féminine delineates corporeal writing, an openness to other(ness), the subversive reading against the masculine knowledge system as the only legacy to be passed on, and the utterance of many voice. It seems natural to regard Namhaegeumsanas a feminine text.

Prominent in Taey’s aforementioned works are her ‘letter-writings’. Her letters are accompanied by different whispering tones, which come from her various transformations and experimentations, and elicit a unique texture, taste and tactile sensation. Letter-writing is an intimate and personal form of writing, even more so than journal writing. It is a literary text work which makes it possible to mix personal stories with public opinion. Letter-writing allowed a liberating form of expression within which nameless women wrote their letters, and signed their names for the first time like ‘writers’. For instance, epistolary novels from the end of eighteenth century to the beginning of nineteenth century, such as Sophie von La Roshe’s Letters to Rosaline (Rosaliens Briefe, 1779/1981), evoke questions of the enlightenment of women, love and class-issues. Epistolary novels were an ideal form for women to discuss the inconsistencies and contradicitions of their social standing and their fascination with their own identities. It is also worth noting that epistolary texts enable multiple points of view through the exchange of letters. Epistolary writing is further relevant to the invention of ‘privacy’ as evidenced by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’s Dangerous Liaisons (Les liaisons dangereuses, 1782).

Taey’s letter-writing contains both these characteristics of epistolary writing. Taey is able to focus on aesthetics and emotion as she attempts to expose the inter-connectivity between private and public realms through a more intimate and less intermediated manner. Letter-writing seems to be a type of methodological guidance in Taey’s art-making. She writes a letter in small florescent marks to signal an aesthetic attempt to signify the inter-subjectivity of language and identity.

Within a given language, the signifier and the signified come to meet coincidentally. Meanings are the result of linguistic behaviors and practices governed by rules and custom. However as Walter Benjamin points out, there is an aspect of ‘expression’ as well as custom in language. Language obtains an ontological dimension instead of functioning simply as social communication. Deleuze illuminates this phenomenon via the concept of transformation from ‘Figure’ (in a relation to Francis Bacon’s painting) to ‘Figural’, in which the language follows the expression of desire, as in poetry and contemporary dance.

In other words, communication is not merely received or sent. Rather, the communication of meanings constitutes a transmission that occurs through a shiver, infection, or stain. Therefore, expressive feelings and the inner aspect of existence become surprisingly contagious, thrilling and stained. Both within the aesthetic experimentation with ‘otherness’, and within the philosophy of sexual identity, there is a tendency to see subjectively through incommensurability instead of seeing singularities. This optic can open the way to new dimensions of existence.

In the work of Fear Note: How to Translate Unspoken Words, the title, “Fear Note”, suggests the linguistic movement of digging into and/or burying the language -- actions that recall the ways a mole digs the ground, or like over-writing on a parchment. Fear Note reveals the contradiction and impossibility of footnotes that arise through a transference of a fear. The fear shows that Taey pushes her work towards an ontological dimension. Fear Note is an appropriate term within which she can express her awareness of borders, living as a familiar stranger in multiple language landscapes. Among all her letters, the letters that most convey longing were written/received during her travels. These letters are received and written at the thresholds of familiarity and strangeness, staying and leaving (Threshold Sea). S/he writes as she is leaving; ‘I won’t write to you again’. Then s/he reads; ‘fear not’. Then s/he writes again on the threshold; ‘I couldn’t find a Shinga – so keep looking for it’.

The space marked by the absence of this place and that place - the space where broken hearts live - in that particular space now drifts towards us a bed in the form of a raft/ a raft in the form of a bed.

The Drifting Bed as a Raft: On the threshold of Aesthetics and Politics

To blind alleys, to cinemas late at night, to empty houses, hurriedly vacated by their occupants, on flowing rivers, under cold bridges, through parks and squares as night turns to morning, I drag around the temporary bed he left behind and try to sleep. The names carved on a spine sucked down into the soaking sheets and mattress... I ride the bed around. I am crossing the thresholds as they turn and grow obscured. Beyond time and space; beyond reality with its repeating revivals and restorations.

- Taey iohe, Restless artist’s statement

Taey Iohe’s solo exhibition, Restless (Trunk Gallery, 5 - 31 Dec 2013), focuses on the image of the ‘bed’. Her performance and video work at Here, There and Everywhere: The Reaction of Art to Urban Life (held at the Geumcheon Art Space in Seoul, as a Community and Research Project, 20 Nov - 10 Dec 2013) emphasises neighbourhood work as an extension of her previous work, Strangers in the Neighbourhood (Golden Threads Gallery in Belfast, Gyeonngi Museum of Modern Art), and Sleepwalkers(Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Stoke Newington Literary Festival), which were made in the district of Hackney in London, and the neighbourhood of Mangwon in Seoul.

In contrast to her neighbourhood work focusing on participation and live interaction, Restless stimulates intimate perceptions and rich imaginings for the audience: each audience member could have a different story to tell about the work. The members of the audience can create their own narratives depending on their work, style and interests in everyday life. Outside the house, on the street, and in the woods, these travelling beds evoke a more imaginative response in the photographs because they stand as they are, without people. The video work Flux of Sleepings shows two women who sleep on a bed while the bed drifts along a stream. However, most of Taey’s photographic work shows the bed alone. Surely the audience cannot but ask, What on earth are these beds doing outside their homes? The bed, in one’s mind, connotes secrets, passions, rest and the body. Showing the body, under the gaze of others, as it changes clothes, rests, makes love, writes diaries and tosses and turns at night tormented by unfulfilled desires, is something unfamiliar, at least to the imagination. Despite the fact that the homeless in every city in the world sleep outdoors every night, the bed is still perceived as a private space secured by four walls. However, even homeless people seek private space. Studies of homelessness reveal social conflicts within homeless society, and among homeless people conflict arises over desirable places that are considered private space, such as under a bridge or a large column, or a space that consists of at least two walls.

But the concept of privacy, which arose in the seventeenth-century and more actively elaborated in the 18th century, was initiated based on the precondition of its violation. Relevant is the connection between the appearance of the novel (a new form of fictional storytelling at the time), middle-class consciousness, the development of modern cities - particularly residential areas - and the expansion of suburban space. People began to think of privacy as an important measure of life and a human right, emphasising individualism, family, life span, and morality. The novel dealt with conflicts and problems of social responsibility in the public sphere, and with personal experience in the private realm. The body became a space where self-examination and middle-class consciousness came into play. The body is a subject itself—an epistemologically productive place from the perspective of the emotional and the desires within fantasy. The body became a space in which different representations and signs could co-exist together.

Solitary, private beings experience a duality as social characters. Private beings emerge from the group to focus on their self-identification, such as their sexuality, by reading and writing in the private sphere. On the one hand, the private sphere is designed to reflect the individual's identity through intimate observation, and with unique meanings that resist any simple and mechanical reproduction and repetition. On the other hand, over-emphasis on private life dilutes the importance of community, which is a foundation of fair play in public society. It is worth noting that the valuation of private life contributed to the rationale behind invention of individual residential areas and middle-class consciousness. In our 21st century, the borderline between private life and non-private life has become diffuse and disjointed.

Neoliberalism’s economic structure and the psychology that derives from it; social media and other platforms that create cyber-relationships; migrants who cross national borders by various means; entertainment industries hellbent on exposing everything lest they lose the interest of their viewers – all of these things have now reduced private life to something of a myth. Within today’s context, Taey’s images quietly observe relationships between private lives and the public sphere - between the intimate and the political. These relationships include the state that takes every chance to peer into the rooms of its citizens (on the pretext of establishing policies on immigration, raising birth rates and reversing population aging); and the people we call “the homeless,” who have nowhere but a cold street corner to rest their heads. Taey’s work engages people who want to overcome the life crises faced by private individuals, by restoring the social and creating communities in spirit and in reality; and encourages people to turn towards the political.

For my work […] it is important to make a space where time and feeling live together; putting an imaginary space into the frame, re-writing the space through this placement, making connections between time and feeling, and finding a new narrative in that transformation. Site-specific works are meant to disappear and be abraded by the passing of time. However [...] in the rim space of everyday life, there are compounds of invisible things; a sensation beyond human feeling, the spirit left behind from nature’s births and deaths, a memory in the objects used by many people, trash from industrial outcomes which do not decay […]. Through my processes, I was looking for an unreal place which does not have much spatial value in society. Anyangcheon, a ghost town in Jichuk, a factory area in Geumcheon, the remains where a house used to be in Sungbuk-dong: These spaces were too empty and rough to imagine romance. But it was the best place to make a new temporarily comforting sleeping place, to create an aching absence. [...] The ‘Flux of Sleeping’ performance was aimed to allow that middle ground between private and public sphere exist together. The rectangular bed approaches the audience as an image of a survival raft.

(from the interview with artist)

An ‘aching absence’ and a ‘temporarily comforting sleeping place’: Absence is void space - because it is still absent in its presence. Beds that shuffle one inch closer into the street, down alleyways and to the edge of the woods each time we turn our heads, in an adult game of Grandmother’s Footsteps. Taey’s beds speak both to those who are only interested in the exterior of how private space is constructed, and also to those who desire to sustain the bed as their own private inner rooms. She asks whether there distinctions exist between a warm comfy bed space and a lover’s warm breathing in bed. Instead, she points out the ‘aching absence’. She talks to us about bodily secrets, the fantasies of desire, and the commodification of passion within neoliberalism. “Come sit down on the bed. Let’s talk here for a little while.”

Taey’s beds become aesthetic and political places. Behind all this, the witch Circe smiles. In ‘Vie Secréte’ by Pascal Quignard, he quotes from Circe in Homer’s Odyssey: ‘If there is a place, it is a bed.’ Circe suggests to Odysseus that they sleep together, though he is doubtful and hostile to her. The action (praxis) of lying down together brings forth a humbleness and trust that are brought into the bed. Confessions spring from unguarded sleep. The bed is a place where all of these could be possible. It is the place to look at each other in nakedness, the place where the obscene reaches a state of communality. It is the place where reality and imagination implode and become permeable in radical ways. What other place could be like this except the bed?

Etymologically, the word ‘private’, which is signified by ‘bed’, stems from ‘privare’, which means ‘bereave or deprive’. Hannah Arendt discusses the way in which “the depriving character of the private lies at the basis of the absence of the others”. Contrary to this, the public sphere includes the world between ‘I’ and ‘the other’. The world starts from the kitchen table, or from the bed. As a kitchen table is designed for sharing food together, ‘bed’ is also a place to sleep together even if someone sleeps alone. René Char, a poet who worked for the French Resistance in World War II, once said, “the chair remains vacant, but the place is set”.

With Taey, we could alter this declaration to read as “the bed remains vacant, but the place is set”. In front of your doorstep, in the blind alleys, in the forest in the dawn, in the cinema you pass by late at night, next to the factory door upon which a poster that informs its workers of its immenent closing blows in the wind - don’t be bewildered if you find an empty bed. You will gradually remember that it is ‘a place’ which used to be there for a reason. In that place, in that bed, you will remember again. The collective unconscious (unbewusste Traumbilder) that you experience in the threshold between sleep and wakefulness - resembles the same collective unconscious that raises your body on the edge of the bed.

Epilogue: “I wish you are here.” - “I am here.”

We pause here, in bed. We have crossed a threshold to make a journey after receiving Taey’s letter. The bed is drifting away somewhere on the stream. It would be nice to sleep there. We lay our tired heads upon the pillow where Mary Wollstonecraft and Hyeseok Na’s names are printed. Our heads shake a little, from the wave of sleeping breath. Our steps become like sleepwalkers as we travel with her and pause. This drifting will not be over. It is okay not to be over. It won’t be done… The arrival will be postponed forever. I won’t be fearful of departing, however. It is important to approach, not to arrive. My journey is to meet your approaching.